News & Press

INSIGHT: Taking Another Look at the Foreign-Derived Intangible Income Deduction

The introduction of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) in 2017 represented a sea of change in how the U.S. taxes companies. One cornerstone of the TCJA is the deduction for Foreign Derived Intangible Income (FDII).

Many new concepts that were introduced in TCJA have names that were meant to go viral (i.e. GILTI, BEAT) and at the time, some of these names were somewhat misleading, which caused confusion amongst taxpayers and practitioners alike when it came to their applicability and calculations. Furthering this confusion is the association between GILTI and FDII, which causes most taxpayers to believe one must own a CFC in order to gain the FDII benefit, but this is simply not true. Among other reasons, many taxpayers dismissed the beneficial FDII deduction in the early days because they thought it did not apply to them. This missed opportunity is a direct result of misunderstanding the oddly named concept.

The concept of this type of deduction for U.S. exports has been around for decades under different incarnations (IC-DISC, DISC, ETI, FSC, etc.). However in the current FDII version, it appeals to a much larger audience than previous deductions.

Additionally, as a result of Covid-19 many businesses have pivoted their products and services to an online distribution model that creates more global sales and potentially more U.S. based intangible income.

What Is FDII?

Foreign Derived Intangible Income may arise when a U.S. company sells products or services to foreign customers and the profit from those sales exceed a hurdle rate for return on assets. Much of the reason that many taxpayers dismissed the notion of this deduction is the “intangible income” misnomer. Typically we think of intangible income as royalties or payments for the use of intellectual property. However in the context of FDII, it is defined as the profit on an export sale above a 10% return on U.S. fixed assets. Thus, any U.S. export profit (regardless of its relation to booked and/or patent registered intangible assets) above this 10% rate of return is treated as “intangible income” and may be able to claim the 37.5% deduction whether or not that excess profit is specifically tied to identifiable intangible assets.

How Does FDII Work?

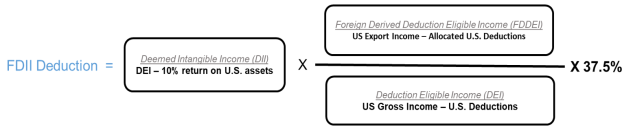

FDII applies to any C-corporation that makes sales or provides services to foreign consumers. This deduction became available for tax years beginning in 2018 and does not apply to any other type of entity. The general FDII formula is as follows:

For U.S. exporters, this essentially yields a 13.125% Effective Tax Rate (ETR) on foreign sales of product, royalties, and services through the FDII deduction. Starting in 2025, this deduction will be reduced to 21.875% which yields an ETR of 16.406%. Additionally, FDII deductions on sales to foreign related affiliates must be scrutinized as the deduction may be further reduced.

Unlike the Section 199 Domestic Production Activity Deductions that only applied to U.S. taxpayers that manufactured in the U.S. (repealed in 2017 under TCJA), the FDII deduction can apply to most any U.S. export revenue as long as they meet two requirements: The sale must be made to a foreign buyer and the product or service must be used outside of the U.S. The documentation of meeting these requirements are described in more detail below.

Practical Matters

If a taxpayer can answer a few basic questions and ultimately can benefit from the deduction, there are two practical areas of scrutiny that taxpayers should focus on 1) documentation and 2) allocation methodology.

(1) Documentation

Some of the original documentation requirements contemplated in the proposed regulations were over burdensome and have just recently been relaxed by Treasury through final regulations, however taxpayers must still take a measured approach when collecting information from the foreign customers to meet the relaxed requirements. In many cases a taxpayer will be able to determine whether it meets the requirements in the final regulations using documents maintained in the ordinary course of its business, as provided in the transition rule.

Within the documentation requirements, we have two pieces of information that must be collected:

Taxpayers must certify that the buyer is foreign and the final regulations provide that the sale of property is presumed made to a recipient that is a foreign person if the sale is as described in one of four categories: (1) foreign retail sales; (2) sales of general property that are delivered to an address outside the United States; (3) in the case of general property that is not sold in a foreign retail sale or delivered overseas, the billing address of the recipient is outside the United States; or (4) in the case of sales of intangible property, the billing address of the recipient is outside the United States

Acknowledgement that the product or service is for foreign use and will not be resold/consumed in the U.S. within 3 years. In general, if an end user receives delivery of general property outside the United States, it will be considered to meet this test. In the case of sales to resellers, a taxpayer must maintain and provide credible evidence upon request that the general property will ultimately be sold to end users located outside the United States This requirement is satisfied if the taxpayer maintains evidence of foreign use such as the following: a binding contract that limits sales to outside of the United States. Certain information from the recipient or a taxpayer with corroborating evidence that credibly supports the information will also suffice.

The U.S. government wants to make sure that taxpayers do not get an export benefit for product that may wind up back in the U.S.

Both of the above documentation requirements may necessitate capturing additional data and may perhaps require some adjustments and additional language in contracts and invoices at the point of sale, however this additional work to substantiate the FDII deduction is likely to be far outweighed by the benefit to the taxpayer.

(2) Allocation methodology

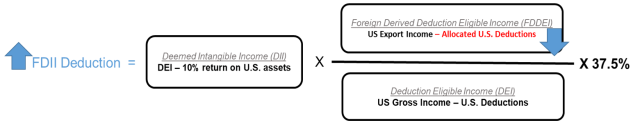

The amount of FDII benefit is a fairly straightforward computation, as noted above. However, there are technical nuances that need to be scrutinized in order to yield the largest allowable benefit. A major component of the calculation is how you allocate general expenses to the FDDEI which is governed under Treas. Reg. Section 1.861-8. The more general expenses you allocate, the lower the FDII benefit:

On its face, if you were to allocate general expenses based on a U.S. domestic/foreign sales ratio this might be the easiest and quickest way to get to your FDDEI. However, with a bit more thought and investigation, a taxpayer might be able to segregate general expenses that are not definitely related to the export sales or come up with a more accurate allocation methodology which could increase your FDDEI and FDII benefit.

For specific expenses like interest and R&D, there may be allocation methodologies that are prescribed by the regulations, but for other general expenses, the methodology could be based on another reasonable basis that is supported by the activity that generates the expense. For larger multinationals, these types of allocations are very similar in scope to what we would be looking at in transfer pricing methodologies and could be looked at similarly.

This intersection of FDII and transfer pricing may also warrant further scrutiny as you may be undervaluing your U.S. based intangibles that could be attracting a higher FDDEI profit. Presumably any additional profit allocated to the US may result in lower GILTI income which needs to be modeled out and understood from a global effective tax rate perspective.

Data Collection: tried and tested approach to a new deduction

We can use another credit/deduction that has been around for decades as a model to collect documentation and information, support the allocation methodology, and to bolster audit defense: the R&D tax credit.

If you are already claiming an R&D tax credit and are familiar with how these studies work, the FDII exercise can be modelled along those lines. For those of you that are not familiar with the R&D credit, here is a brief summary of how data is collected and how the credit works:

What Is the R&D Tax Credit?

The federal research and development tax credit, also known as the research and experimentation (R&E) tax credit, was first introduced by Congress in 1981. The purpose of the credit is to incentivize U.S. companies to increase spending on research and development within the U.S.

The R&D tax credit is available to businesses of all sizes in a wide variety of industries that uncover new, improved or technologically advanced products, processes, principles, methodologies or materials. In addition to “revolutionary” activities, in some cases, the credit may be available if the company has performed “evolutionary” activities such as investing time, money and resources toward improving its products and processes.

Correctly calculating the R&D tax credit is critical because the credit can be used to lower the effective tax rate a company pays and to increase cash flow.

How does the R&D Tax Credit work?

The R&D tax credit is available to taxpayers who incur incremental expenses for qualified research activities (QRAs) conducted in the US. The credit is comprised primarily of the following qualified research expenses (QREs):

(1) Internal wages paid to employees for qualified services; this includes those individuals directly performing the science as well as those individuals supporting and supervising these individuals.

(2) Supplies used and consumed in the R&D process.

(3) Contract research expenses (when someone other than an employee of the taxpayer performs a QRA on behalf of the taxpayer, regardless of the success of the research.

(4) Basic research payments made to qualified educational institutions and various scientific organizations.

For activities to qualify for the research credit, the taxpayer must show that it meets the following four tests:

(1) The activities must rely to on a hard science, such as engineering, computer science, biological science or physical science.

(2) The activities must relate to the development of new or improved functionality, performance, reliability or quality features of a structure or component of a structure, including product or process designs that a firm develops for its clients.

(3) Technological uncertainty must exist at the outset of the activities. Uncertainty exists if the information available at the outset of the project doesn’t establish the capability or methodology for developing or improving the business component, or the appropriate design of the business component.

(4) A process of experimentation (e.g. an iterative testing process) must be conducted to eliminate the technological uncertainty.

Once it is established that the activities qualify, a thorough analysis must be performed to determine that the taxpayer has assumed the financial risk associated with, and will have substantial rights to, the products or processes that are developed through the work completed.

At the Intersection of FDII and R&D tax credits—The Benefits

Appropriate documentation for claiming the research credit may require changes to the company’s recordkeeping processes because the burden of proof regarding all R&D expenses claimed rests with the taxpayer. The R&D tax study necessitates the development of a methodology to identify, quantify and qualify project costs that are eligible. This is accomplished through a detailed interview regimen of key company personnel and an analysis of company financials. The results include detailed qualitative questionnaires that marry-up the tax law with the development/manufacturing efforts the company is undertaking. In addition, quantitative mathematical models are developed that track expenditures utilizing wage data (W2- Box1) in conjunction with detailed time allocation sheets. Employee time is qualified as either direct, support or supervision of R&D or alternatively as NQ – not qualifying. The current R&D study can be modified to accommodate the requirements of an FDII study. This approach allows completing both analyses at once, minimizing business disruption while taking advantage of two tax optimization tools.

This additional benefit is achieved by implementing a singular, expanded analysis. The singular, expanded analysis approach achieves this benefit because the FDII benefit calculation and the R&D credit calculation have similar requirements, including but not limited to:

- Detailed tracking of time keeping,

- Specific receipts of proof,

- Specified allocations or expenses,

- Patent and IP records

- Detailed records of employee wages/salaries,

- Detailed record of high-level executives time allocation and responsibilities, and

- Detailed mapping of services provided (to, from, when, where, concerning what)

Because of this overlap in necessary documentation and information, suggested future recordkeeping provided as a result of the analysis will be cohesive and ultimately easier to implement at once as opposed to a piecemeal approach

Other Issues to be aware of: Caveats

The FDII deduction may intersect with other potentially complicated areas of tax law, so determining the maximum benefit will depend on other factors of a taxpayer’s tax positions. GILTI and FDII are very closely related and can be viewed as different sides of the same coin, thus positioning on FDII will likely affect the outcome of GILTI, and vice versa.

In these uncertain times, usage of NOL carrybacks may also affect the amount of FDII deduction that is available as you must be in an income position to take the deduction.

The past incarnations of this deduction (DISC, IC-DISC) have been challenged by the World Trade Organization as export subsidies, so we might see the same challenges being raised, however, this should not deter taxpayers from taking the benefit while it is available.

There are more than a couple dozen states that have allowed the FDII deduction, thus there is potentially additional rate benefit that should be considered.

Careful thought needs to be considered as to how taxpayers can manage their tax attributes properly and preserve them for as long as possible. In most cases, a balancing act to maximize credits and deductions can be achieved through comprehensive modeling.

To-Do Checklist

Step 1: The first available deduction was in 2018, so checking to see if you are eligible is the first step. If you were eligible and took the deduction, looking at it a second time to understand the allocation of expenses and documentation of foreign buyer/use is the next step.

Step 2: Audit defense – Are you prepared for an audit and do you have the required documentation?

Step 3: Evaluating your operating/sales structure to see if there is additional benefit that can be obtained by routing transactions differently? This requires more analysis and in-depth understanding of the business beyond taxes but could be a valuable exercise to determine if there is opportunity to lower global tax rate by structuring into FDII (i.e. US global distributor taxed at 13.125%).

Step 4: Building templates to document and quantify the relevant data and information in a proactive fashion.

Read the original article on Bloomberg Tax